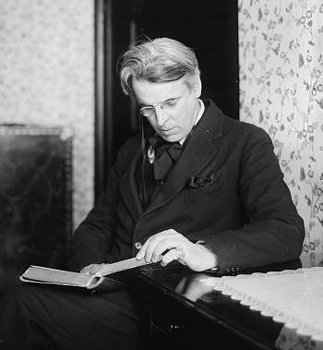

The Two Treesby: William Butler Yeats (1865-1939)Written and published in 1893, The Two Trees is one of many poems Yeats wrote to Maud Gonne. Yeats met Gonne, a tall, beautiful 23-year-old heiress, artist and Irish Nationalist, in 1889 and developed an obsessive admiration for her beauty and outspoken manner. This infatuation is believed to have had a major impact on both Yeats poetry and life as a whole. The Two Trees is a contrast of Gonne’s inward and outward beauty. He begins the poem off: “Beloved, gaze in thine own heart, the holy tree is growing there”. Here Yeats is telling Gonne to understand why he loves her; she needs to look self-analysis the spirit of her nature (the holy tree). The second stanza starts with, “Gaze no more in the bitter glass…” in which Yeats is telling her not to be concerned with looks or outward appearance for they will fade in time. He wants her to love herself for the qualities she posses on the inside, much like he does. It is believed that the two trees that Yeats refers to in this poem are the tree of knowledge and the Sephirotic tree of the Kabblah. Both of the trees are often referred to as the holy tree, which he tells Gonne she has growing inside.

|

The Two TreesBELOVED, gaze in thine own heart, Gaze no more in the bitter glass |